"What do the -san, -chan, -kun, etc titles

at the ends of names mean?"

"What about 'sempai' and 'kouhai?'"

"How about 'niisan', 'baasan,' and stuff

like that?"

"Then how do 'shounen' and 'shoujo'

compare?"

Everyone who's ever seen Karate Kid (and that's basically

all of America) knows that the Japanese like to stick -san at

the end of people's names. Anime fans also learn that there are more suffixes

than -san, mainly -kun, -sama, and -chan

too. The problem is that they learn these suffixes from anime, and the language

used in anime does not equal the language used in real life.

So here's a rundown of the way these suffixes are used in actual Japanese.

Hopefully this will keep more American anime fans from mis-using or over-using

certain suffixes, and either sounding comically swishy, or offend an actual

Japanese person.

Note that I include the little dashes " - " before the suffix. There

are no little dashes like that in written Japanese. Putting a dash before the

suffix has become standard in English, so that clueless Americans will understand

that it's not part of the person's actual name. If you were writing purely in

Japanese, you would add the suffix without any dash or space.

An important note before you continue reading:

Anime/manga is entertainment. In entertainment, you are dealing not with real

people, but with caricatures. Think about this carefully. Please do not

simply nod and dismiss it. You are able, as a viewer, to get a deep understanding

of a character's personality and history by only "knowing" them for

a very brief amount of time. This is accomplished by giving them "defined"

characters with "defined" relationships, and having them stick to

it in virtually all situations.

Japanese name suffixes are an expression of not only personality, but also

imply a great deal about the relationship between speaking and listener. In

anime, characters typically favor one suffix to refer to someone and stick with

it in order to establish personality/relationships quickly, so that the

plot can move forward.

In real life, this will prove disastrous. In real life, you must change your

suffix choice depending on who you're talking to, and the situation at hand.

Please do not try and imitate your favorite anime character by using one suffix

religiously. At best, you will be thought of as strange. At worst, you will

actually offend someone. Regardless, Japanese people are so very polite they

likely won't tell you either.

So with that... moving right along.

|

|

Everyone knows -san. In Japanese, you must attach

a suffix to someone's name unless you're very close friends, and san

is the most basic. You can forget trying to translate it. Some people

claim it's like calling them "Mr." or "Mrs." so-and-so,

but there are other suffixes which are better suited for that, and san

is less a term of a respect than obligatory.

San is completely neutral, straight and level on the

politeness scale. In real life, easily 75% of all the suffixes ever

used are going to be san. Nextdoor neighbors are san

to each other, fellow employees are san, friends you've

made as adults (that you haven't grown up with) are also going to be

san. Anime fans love to drop san in favor

of kun or chan as soon as they learn them

-- this doesn't work in Japan. You're going to either sound feminine,

or insulting. Stick with san unless a Japanese person

basically shows you that it's okay to use something else.

"But I'm an American! I don't like formality. I like to drop to

the informal as soon as possible." The average Japanese person

simply doesn't care. You are making a statement about what you think

about them. The important thing is in how they interpret it. So please

don't try and make a statement about your own personality by not using

san when you need it - it will backfire.

|

|

|

Sama is actually where san came from,

but people got lazy in the pronunciation centuries ago. (That's why

sama has a kanji character but san doesn't.)

These days, sama is a statement of extreme politeness,

respect, and esteem. Someone you look up to, or the lord of a castle,

or your company CEO, would be sama. This part is already

widely known, even by anime fans.

The part that isn't as widely known: in Japanese culture, you are

supposed to default to sama when talking to someone

anonymously. Why? You can't risk offending them if they turn out to

be someone you should be using sama with. You can't

go "Oops, sorry, I didn't know you were the President of Sony"

in Japanese. This is why people answering the telephone, announcements

in train stations, letters where the recipient is unknown, anything

that will be reaching the ears of people with unknown social status

all use sama.

|

|

|

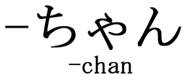

Chan. Hideously overrused by American fanboys. Little

kids and babies in Japan have a hard time making proper S

sounds, and will often slur them. For example, sakana

(fish) becomes chakana, sensei becomes shenshei,

etc.

This is where chan came from, as a baby pronunciation

of san. Keep in mind how diminuitive this is when you

use it. It has a strong aura of "cuteness" and femininity

to it. You can use it both for little boys and girls up until about

the age of 8 or 9. After that, you should stick to only using it with

cute little girls.

Yes, a number of guys use chan for themselves. I promise

you that as a foreigner, you can't get away with this. Japanese males

using chan have other ways within the language of establishing

that they are male. If your Japanese is still fairly gender neutral

textbook Japanese, and you use chan, many people

will consider you comically swishy.

Any adolescent boy or older is going to get very upset if you

use chan with their names, (unless you happen to be an

attractive woman using it in a playful flirtatious way.) Girls use chan

with one another constantly, even into adulthood, but boys tend to drop

it at an early age. Don't use chan unless you're very

close to the person and have heard them use it before, or unless you're

an adult trying to talk to a kid, like a teacher to their 1st or 2nd

grade student. Always error on the side of caution before pushing

chan on someone who may not appreciate the connotation. Yes,

it is used all the time in anime. Anime is not real life. Please don't

over-use it.

|

|

|

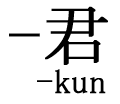

Kun is mis-used almost as badly as chan.

Most websites simply say that kun is the boy's version

of chan. Aaaalmost, but not quite.

Kun is usually attached to boys' names, however next

exclusively. It implies one of two things: 1) the person is a male who

you consider yourself very close to. Or 2), They are significantly below

you in social standing. Note the last one. Using kun on

someone who does not expect it will be interpreted this way. Be careful.

Many American fanboys like to attach kun even to the

names of people they don't know. "Look how casual and friendly

I am!" No. Do not do this. If you attach kun to a

stranger's name, they are going to interpret it as in #2 above, and

take it as an insult. The rules are slackening, and it's becoming more

widely accepted to use kun even among regular guy friends

that you haven't known since childhood, but it's always safer to not

use it until you receive some signal that it's okay.

|

|

|

Sensei is easy. Historically, sensei was

used only to refer to medical doctors and professors. These days, sensei

can be used with anything who teaches anything. I've heard

professional athletes call their coaches sensei, manga

artists call their role model artists sensei. I've even

read interviews where fashion models will call their older, more experienced

model friends sensei.

|

|

|

Dono is an odd one, and not heard too often. Dono

is an archaic, highly formal way of addressing someone, similar to the

feeling of "sir," or "m'lady," or what have you.

Respectful, polite, but obscolete.

You will still see dono used in official documents, especially

if they are religious in nature or highly formalized. Otherwise, it's

mostly disappeared.

|

|

|

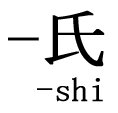

People often say that san is like "Mr." or

"Mrs.", but shi comes a lot closer to this feeling.

Shi is used almost exclusively in business contracts,

newspaper articles, etc. It is 3rd person. This means you can't attach

it to the name of someone you're talking to directly. In that case,

it would be best to use san or sama. However,

it's still important to know if you're ever reading something in Japanese

that is more formal than manga or intro level textbooks.

|

|

|

Kyou. This is an official title similar to Sir or Lord.

It is seldom used now that Japan has become a full democracy, however

up until the Meiji Restoration (1870ish), it was used for government

leaders, ministers, and advisers.

These days, it is rarely if ever used for anyone. Foreign dignitaries

will usually be referred to with their title, not with kyou.

However you will still see it used in older settings to refer to people

like government officials.

|

Q: Then what do "sempai"

and "kouhai" mean?

|

|

Senpai (it's also sometimes spelled sempai

in English, although it's technically an N) means someone

who "came before" and kouhai means someone who

"came after." In any organization, whether it's the military,

a karate club, or a basketball team, there will be people who joined

before you, and people who joined after you. Senpai is

often used as a name suffix. Kouhai is not, but the two

words form a pair so I included both.

In Japan, this is a big deal. Senpai are to be treated

with respect. In return, they traditionally treat their kouhai

with care and look out for them. In Japanese society, this fosters an

extreme sense of belonging, where everyone has their own set of senpai

and kouhai, and in turn they form a chain of friendship

that keeps the group together. Traditionally, even if it was something

as trivial as, say, the school's Aikido team, senpai

watch out for their kouhai, providing them with help even

outside of the club, and kouhai treat their senpai

with mutual respect. Ideally, everyone comes away from the experience

with a sense of worth, obligation, and friendship, however in any society

you are going to have the occasional person who abuses the system. Senpai

mistreating their kouhai always makes big news outside

of Japan, and contributes to the stereotype of Japan being a harsh,

rigid society. In actuality, this is very rare.

For better or for worse, this is slowly fading in Japan. High school

and college-level athletic teams still maintain the strong senpai/kouhai

relationship. Martial arts dojos are probably the strongest remaining

places where senpai/kouhai is used outside of the workplace.

Otherwise, clubs and organizations are becoming more lax, and more individualistic

like their Western equivalents.

The point is:

Name suffixes make statements about senpai/kouhai relationship. Using

a diminuitive suffix that the other person is not expecting will make

it sound like you consider yourself the senpai of the relationship.

This can be disastrous if the other person does not consider themselves

your kouhai. This is why you must be careful.

|

|

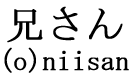

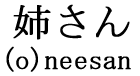

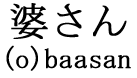

Q: What's with people

calling each other "nii-san" or "baa-san" and stuff? I thought

these meant "older brother" or "grandma" or what have you?

A: Technically that's exactly what they mean. However,

in Japanese, you can use them to refer to people within certain age groups even

if they're not related to you.

Note that you're supposed to attach o- to

the front of these to make them polite titles. This is often not done. Also,

you can replace the san at the ends of them with chan

or sama to change the tone and politeness level.

Also, you'll see that jiisan/jisan

and baasan/basan look nearly identical in English letters. This

is the difference between a single-long and double-long vowel in Japanese. I

can't explain entirely what that means here, but they are different words

and are pronounced differently.

|

|

Niisan is used to refer to young men. It technically

means someone's older brother. There's no hard, official age limit on

who you can call niisan, but it's basically between adolescence

and middle age. If you're a guy within this age group, don't be suprised

if a little kid calls you niisan or niichan.

They're not trying to say you're their older brother. It's just a way

of referring to young men within that age group, especially if you don't

know their name. It's not even considered rude. It's as neutral as calling

someone "young man."

|

|

|

Neesan is the female equivalent of niisan.

It technically means older sister.

|

|

|

Obasan technically means "aunt" and is used

to refer to people who are middle aged, but not yet elderly. Note that

long ago, age was a good thing in Japan, and people were proud

to be called obasan instead of neesan. In

recent years, however, this has changed. People will be irritated if

you use obasan before they're well into middle-age. People

like to hang on to neesan as long as possible.

Note that the o in front of this one is mandatory. The

pronunciation is off without it. There are kanji for this, but they

are rarely used.

|

|

|

Ojisan (uncle) is the male equivalent of obasan.

Everything that applies to obasan applies to ojisan.

Some people might not be terribly thrilled about being refered to as

ojisan before they're ready to admit it. Note that the

o in front of this one is also mandatory. Pronunciation

just doesn't work without it. There are kanji for it, but they are rarely

used.

|

|

|

Baasan means grandmother, and refers to someone past

middle age. It is very common to hear baachan instead

of baasan, because of the image of a cute, doddering woman

in her twilight years. Again, age has historically been something to

be proud of in Japan, so this isn't considered rude. These days though,

calling a woman baasan before she is actually elderly

is going to really irritate her.

Babaa is the rude way to refer to an old woman. Nasty

old ladies, witches, etc, will get people referring to them as baabaa.

|

|

|

Jiisan means grandfather, and is the male equivalent

of baasan. Again, it's also changed to jiichan

to refer to little, cute, doddering old men, but I guarantee you'll

find fewer elderly men who appreciate this image than women.

Jijii is the rude way to refer to an old man. Nasty old

men who grope women on trains, and sit on park benches and yell at random

passerbys are likely going to be referred to as jijii.

|

Q: Okay, then what

about "shounen," "shoujo," and words like that? Are those

like nii-san and nee-san?

A: Sort of. Not really.

|

|

Shounen is written with the two kanji for "little"

and "years." Essentially this means a young boy between the

ages of 10 to 20 or so. What ages constitute shounen change

depending on which person you ask. Shounen is different

from niichan because it isn't a title. It's a noun. You

can't stick it on the ends of names. (Yoshi-niisan works, Yoshi-shounen

is comically wrong.) It's used exclusively to refer to a 3rd person

within that age group, or as a reference to a target age group, such

as the magazine Shounen Jump. Here it's showing the target

age group for the magazine.

|

|

|

Shoujo is written with the two kanji for "little"

and "girl." Why do boys get "little" and "years"

but girls have to use "little" and "girl?" The best

guess is that shoujo came along as a word after shounen

was already in wide circulation to refer exclusively to boys, so they

had to use "girl" to show the difference.

Again, this is a noun, not a title, just like shounen.

|

|

|

Seinen requires a bit of explaining. The two kanji are

"blue" and "years." The color blue in historical

Japanese is very strongly tied to sex, life, and reproduction in a very

vague, we're-sort-of-saying-it-but-not-quite, nudge-nudge wink-wink

say-no-more, sort of way. I dare you to count how many songs use the

color blue in a suggestive way.

Seinen therefore refers to a young man, slightly older

than shounen, who's around the age where historically

he would be working on the whole "blue" thing. This is pre

middle-age, but post adolescence.

No, this is not a risque term. It's completely acceptable to use in

all situations.

|